Biography

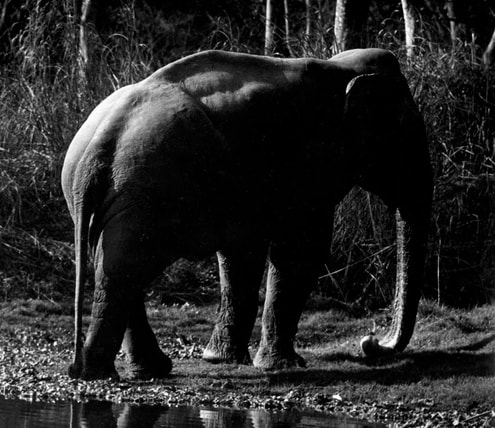

M. Krishnan (1912 – 1996) was an artist, writer, wildlife photographer and one of India’s finest naturalists of his time. He spent months in the forests of India, recording his observations with pen and camera.

Early Life

He was born in Tirunelveli on 30th June 1912 to A. Madhaviah and Meenakshi and was the youngest of eight children. Madhaviah worked for the British Government in the Salt and Abkari department. He was a distinguished writer and social reformer who published novels both in English and Tamil. Krishnan and his siblings admired their father and grew up with a deep appreciation for English and Tamil literature and the arts. Madhaviah passed away when Krishnan was only thirteen and Krishnan always spoke of him with much love and appreciation for his literary work and the social principles he stood for.

Krishnan spent his early life in Chennai (then Madras) and attended the Hindu High School. He later went to the Presidency College, Madras from 1927 to 1933. Never a good student, Krishnan managed to just pass both his BA and MA in Botany. Madras, unlike now, boasted much flora and fauna and Krishnan grew up a keen observer of nature, with an interest in drawing, painting and writing. His older sister, Lakshmi took on the responsibility of looking after the family after their father’s sudden and premature death. Madhaviah had brought her back very soon after her marriage when he found that she was being ill-treated by her husband’s family. He educated her and she was Professor of English at the Queen Mary’s College for Women, Madras. She nurtured and encouraged Krishnan’s interests in the arts.

Early Life

He was born in Tirunelveli on 30th June 1912 to A. Madhaviah and Meenakshi and was the youngest of eight children. Madhaviah worked for the British Government in the Salt and Abkari department. He was a distinguished writer and social reformer who published novels both in English and Tamil. Krishnan and his siblings admired their father and grew up with a deep appreciation for English and Tamil literature and the arts. Madhaviah passed away when Krishnan was only thirteen and Krishnan always spoke of him with much love and appreciation for his literary work and the social principles he stood for.

Krishnan spent his early life in Chennai (then Madras) and attended the Hindu High School. He later went to the Presidency College, Madras from 1927 to 1933. Never a good student, Krishnan managed to just pass both his BA and MA in Botany. Madras, unlike now, boasted much flora and fauna and Krishnan grew up a keen observer of nature, with an interest in drawing, painting and writing. His older sister, Lakshmi took on the responsibility of looking after the family after their father’s sudden and premature death. Madhaviah had brought her back very soon after her marriage when he found that she was being ill-treated by her husband’s family. He educated her and she was Professor of English at the Queen Mary’s College for Women, Madras. She nurtured and encouraged Krishnan’s interests in the arts.

Krishnan grew up a keen observer of nature, with an interest in drawing, painting and writing.

Professor Fyson

One of Krishnan’s teachers, Professor P.F. Fyson who was Chief Professor of Botany, was an important part of Krishnan's college life and had a significant influence on him in his impressionable years. Krishnan always spoke of

Mr Fyson with affection and respect and recalled how Mr. and Mrs. Fyson referred to him as their “Indian son”. Professor Fyson took great interest in the flora of the South Indian hills and published many illustrated books about the flora of the Nilgiris, Kodaikanal and Yercaud. Mrs. Fyson (Diana Ruth Fyson) accompanied Mr. Fyson and his students on their plant collection trips, helping with her skilled water color illustrations. Krishnan shared with Mrs. Fyson an abiding interest in water color painting, line drawing and putting together picnic lunches, acquiring a proficiency in these skills that he retained to the end. Krishnan's informal friendship with Fyson did not come in the way of doing badly in both his degree exams.

Krishnan’s trips in and around Sandur, in the countryside and forests, gave him much pleasure and satisfaction.

Move to Sandur

Krishnan went on to study law at the Law College, Madras from 1934 to 1936. As he did not do well in college, he found it difficult to get a job. After a brief apprenticeship course in the court, he took on a job as Chief Artist at Associated Printers, had a brief spell at the Madras School of Arts and then worked as Publicity Officer in All India Radio (AIR), all in Madras. He married Indumati Hasabnis in 1937 and they had a son, Hari, in 1938. Over the next two years, his wife’s health took a turn for the worse and she lost a lot of weight. The doctors she consulted gave her the advice customary for the times, to move away from the city to a drier, quieter place. Her father who had lived in Sandur (near Bellary) and knew the ruling family of the Raja there, suggested it as a place that might be suitable. Krishnan resigned from his job at AIR and moved to Sandur with his family where he joined the Sandur State Service late in 1941. He worked in Sandur until 1950, beginning as a teacher in the local school, moving on to serve as a judge and later as publicity officer before finally becoming the political secretary to the Raja of Sandur. Sandur was then a quiet town and lacked electricity, except for four hours in the evening. Krishnan found the work dreary and tedious at best and his work became stressful in his later years in Sandur because of the negotiations princely states had with the Indian government after India’s independence in 1947.

However, Krishnan’s trips in and around Sandur, in the countryside and dry deciduous forests, gave him much pleasure and satisfaction. There were sambar, wild boar and the occasional thrill of a leopard in the forests and several smaller animals like four-horned antelopes, jackals, jungle cats, porcupines, hares, and many birds including peafowl. At home, Krishnan reared goats and homing pigeons and managed to scandalize his professional colleagues when he took time off to graze his goats. He always had dogs, and in Sandur he had one of his favorites, a Rajapalayam called “Chokki”. The years spent in Sandur were very rewarding to Krishnan in terms of his experience with wildlife. He began writing about the animals and plants around him for the Hindu newspaper (under the pen-name “Z”) and for the Illustrated Weekly of India. His writings were always accompanied by his pen-and-ink or water color paintings, in his rather distinctive style.

Krishnan went on to study law at the Law College, Madras from 1934 to 1936. As he did not do well in college, he found it difficult to get a job. After a brief apprenticeship course in the court, he took on a job as Chief Artist at Associated Printers, had a brief spell at the Madras School of Arts and then worked as Publicity Officer in All India Radio (AIR), all in Madras. He married Indumati Hasabnis in 1937 and they had a son, Hari, in 1938. Over the next two years, his wife’s health took a turn for the worse and she lost a lot of weight. The doctors she consulted gave her the advice customary for the times, to move away from the city to a drier, quieter place. Her father who had lived in Sandur (near Bellary) and knew the ruling family of the Raja there, suggested it as a place that might be suitable. Krishnan resigned from his job at AIR and moved to Sandur with his family where he joined the Sandur State Service late in 1941. He worked in Sandur until 1950, beginning as a teacher in the local school, moving on to serve as a judge and later as publicity officer before finally becoming the political secretary to the Raja of Sandur. Sandur was then a quiet town and lacked electricity, except for four hours in the evening. Krishnan found the work dreary and tedious at best and his work became stressful in his later years in Sandur because of the negotiations princely states had with the Indian government after India’s independence in 1947.

However, Krishnan’s trips in and around Sandur, in the countryside and dry deciduous forests, gave him much pleasure and satisfaction. There were sambar, wild boar and the occasional thrill of a leopard in the forests and several smaller animals like four-horned antelopes, jackals, jungle cats, porcupines, hares, and many birds including peafowl. At home, Krishnan reared goats and homing pigeons and managed to scandalize his professional colleagues when he took time off to graze his goats. He always had dogs, and in Sandur he had one of his favorites, a Rajapalayam called “Chokki”. The years spent in Sandur were very rewarding to Krishnan in terms of his experience with wildlife. He began writing about the animals and plants around him for the Hindu newspaper (under the pen-name “Z”) and for the Illustrated Weekly of India. His writings were always accompanied by his pen-and-ink or water color paintings, in his rather distinctive style.

He began writing “The Country Notebook” in the Statesman, Calcutta, which was published without a break for

forty-six years.

Writing and Photography

In 1950, after Sandur ceased to be a princely state, Krishnan settled down in Madras. He was not yet forty then and he declined an offer of a good Government job, opting instead to follow his own bent and be a freelancer. He took to writing full time for The Hindu, The Illustrated Weekly of India and Shankar’s weekly contributing essays on wildlife, culture and art, cricket, verses, and short stories. He began writing a fortnightly column, “The Country Notebook” in the Statesman, Calcutta, which was published without a break for forty-six years, the last column appearing the day he died.

During this time, he did not make much money and in fact found it quite hard to make ends meet. He nevertheless soldiered on and around 1954, he added photography to his skills. One of his earliest cameras was a Super Ikonta by Zeiss-Ikon. He also had a Voightlander and he soon became interested in the assembly of cameras. He preferred black and white film to color as the medium in which he could express himself best. He also favored roll film over 35 mm film for its much larger negatives, which he could enlarge to produce big, sharp exhibition prints ranging in size from 20” x 30” to 30” x 40”. The wealth of detail that showed up in such large pictures enhanced their obvious visual appeal and Krishnan took pride in his ability to produce them.

Krishnan was awarded the Jawaharlal Nehru fellowship (1968-1970) for an Ecological Survey of the Mammals of

Peninsular India. His work for the fellowship was published as India’s Wildlife, 1959-70 (BNHS) in 1971.

Krishnan was awarded the Padma Shri in 1970 in recognition of his work on wildlife conservation for the country.

Wildlife Work, Contributions and Recognition

By the end of the 1950s, Krishnan’s had earned the reputation of being a committed naturalist. He served for decades on diverse Government of India Wildlife Committees and was one of the founding members of the Indian Board for Wildlife. He traveled extensively in the 1960s, surveying the forests all over India and taking photographs. Following this, Kodak organized an exhibition of Krishnan’s wildlife pictures in 1966 in Madras.

In 1968, the first year the Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Fund began granting fellowships, he was awarded the Jawaharlal Nehru fellowship (1968-1970) for an Ecological Survey of the Mammals of Peninsular India. His work for the fellowship was published by the Bombay Natural History Society as India’s Wildlife, 1959-70 (BNHS) in 1971. Krishnan was awarded the Padma Shri in 1970 in recognition of his work on wildlife conservation for the country. In 1972, he was one of the founding members of the Steering Committee of Project Tiger, formed to conserve the declining tiger population.

Besides undertaking wildlife surveys for various states in India, Krishnan wrote guidebooks for the Vedanthangal and Mudumalai Sanctuaries of Tamil Nadu, the Bandipur Tiger Reserve of Karnataka and Corbett Park in Uttar Pradesh. He wrote and published books on wildlife and also wrote two books of fiction.

Locally, Krishnan was one of the founding Trustees of the Madras Snake Park (now the Chennai Snake Park) and was involved in setting up the organization. He was always available to talk to members of the Madras Naturalist Society, many of whom visited him at his home. Krishnan would offer them tips about photography and wildlife areas to visit. He contributed articles and photographs to their journal Blackbuck.

Krishnan continued writing about wildlife and occasionally about other topics that interested him, contributing to several Indian publications. He worked single-handedly in his arduous effort to conserve India's flora and fauna, using every means available to him.

In 1995, Krishnan was nominated to the Global 500 Roll of Honour of the UNEP (United Nations Environment Program) for, in his words, “close on half a century’s continuous effort in trying to inform and stimulate an interest in the public in India’s stupendous heritage of wild flora and fauna, being steadily depleted.”

Krishnan worked hard until he passed away in 1996. His legacy lives on in the many people he encouraged and inspired to take an interest in India’s wildlife.

In 1995, Krishnan was nominated to the Global 500 Roll of Honour of the UNEP (United Nations Environment

Program) for, in his words, “close on half a century’s continuous effort in trying to inform and stimulate an interest in

the public in India’s stupendous heritage of wild flora and fauna, being steadily depleted.”

Copyright © 2019